18th-century naturalist practices merged with machine learning, transforming minerals, matter, and field observations into computational insight.

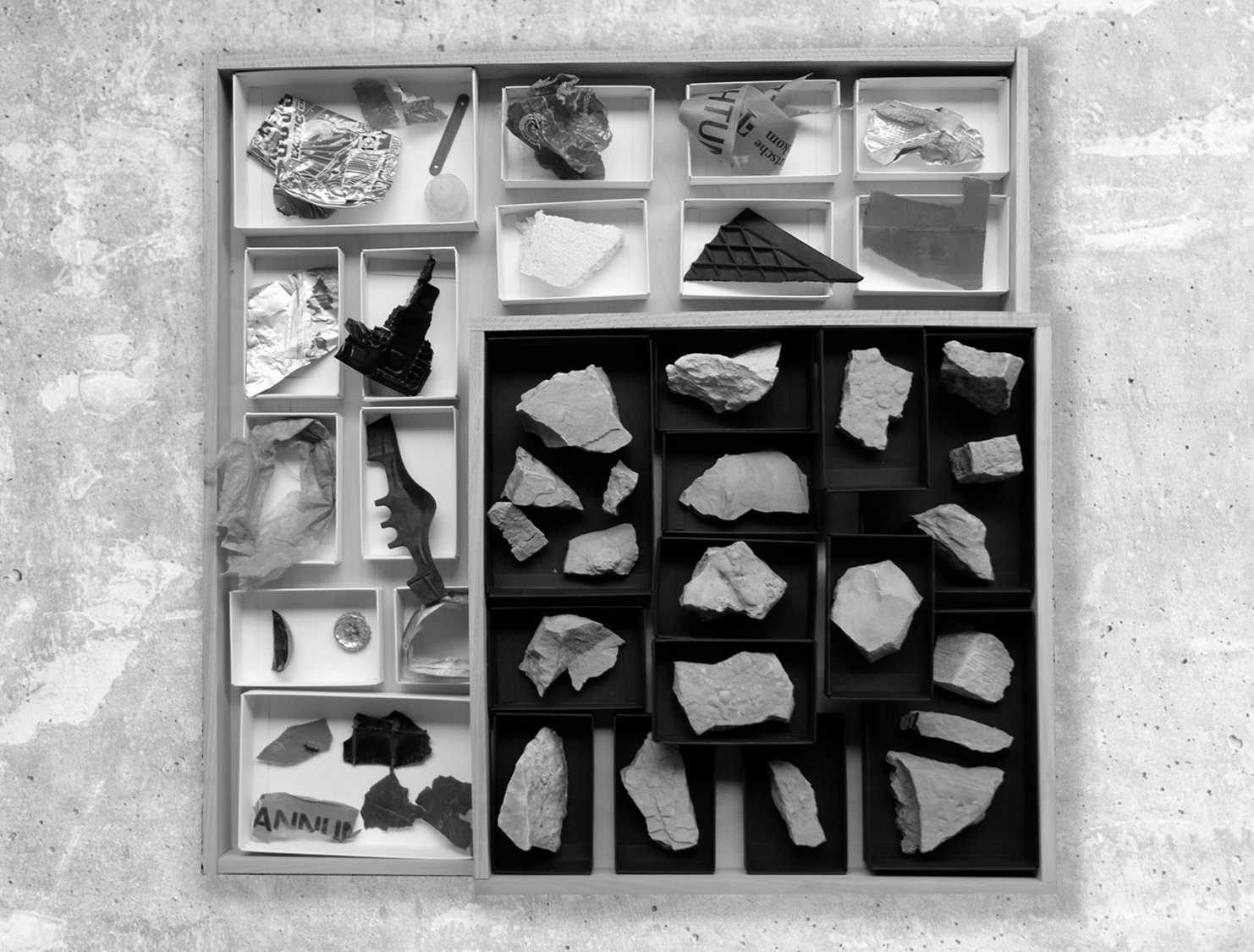

In the process of crafting this atlas, samples of both natural objects (rocks) and human-made materials are collected during expeditions to geological sites. These items are transformed into specimens used to train machine learning models, enabling the exploration of the latent space bridging the natural and the artificial. The result—a collection of hybrid digital artifacts—is annotated by image classifier algorithms that are available to the public.

This atlas was initiated by New York/Berlin-based media artist Pascal Glissmann in 2018. The development is in progress—new collections/ albums/ plates and minerals are generated continuously.

In the process of crafting this atlas, samples of both natural objects (rocks) and human-made materials are collected during expeditions to geological sites. These items are transformed into specimens used to train machine learning models, enabling the exploration of the latent space bridging the natural and the artificial. The result—a collection of hybrid digital artifacts—is annotated by image classifier algorithms that are available to the public.

This atlas was initiated by New York/Berlin-based media artist Pascal Glissmann in 2018. The development is in progress—new collections/ albums/ plates and minerals are generated continuously.

— Material & Existence

An Atlas of Mineralogy is an illustrated inventory of the inanimate material forming the Earth's surface. Throughout history, humans have been driven by the desire to gain a deeper understanding of this surface, as it directly connects to our existence.

James D. Dana articulates this idea in his publication "Manual of Mineralogy" (1857), stating, "The very existence of many of the arts of civilized life depends upon the materials which the rocks afford." However, our motivation extends beyond pure scientific curiosity. There exists a profound, almost mystical fascination. Dana observes, "The student of Mineralogy (…) finds abundant pleasure in examining the forms and varieties of structure which minerals assume." He emphasizes the role of our senses: we observe, touch, smell, and, at times, even taste to expand our understanding of the world through the medium of rocks.

Modern technology extends our senses: satellites enable us to study our planet's surface from the orbit; x-rays and electron microscopy offer a glimpse into the inner composition of rocks; and digital networks enable a simultaneous comparison of global shifts in geology.

An Atlas of Mineralogy is an illustrated inventory of the inanimate material forming the Earth's surface. Throughout history, humans have been driven by the desire to gain a deeper understanding of this surface, as it directly connects to our existence.

James D. Dana articulates this idea in his publication "Manual of Mineralogy" (1857), stating, "The very existence of many of the arts of civilized life depends upon the materials which the rocks afford." However, our motivation extends beyond pure scientific curiosity. There exists a profound, almost mystical fascination. Dana observes, "The student of Mineralogy (…) finds abundant pleasure in examining the forms and varieties of structure which minerals assume." He emphasizes the role of our senses: we observe, touch, smell, and, at times, even taste to expand our understanding of the world through the medium of rocks.

Modern technology extends our senses: satellites enable us to study our planet's surface from the orbit; x-rays and electron microscopy offer a glimpse into the inner composition of rocks; and digital networks enable a simultaneous comparison of global shifts in geology.

— Naturalists & Machine Learning

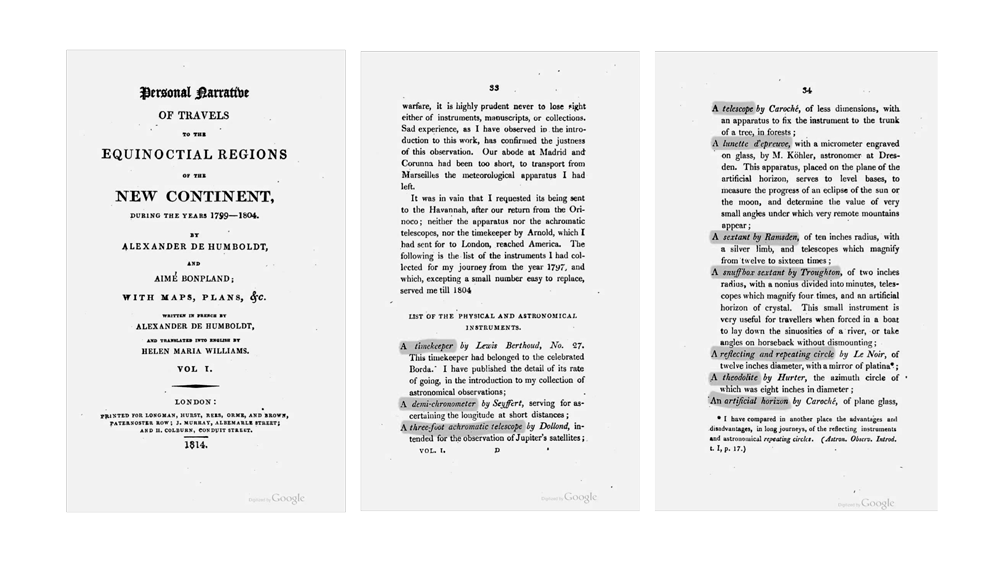

Scientific atlases of the 18th and 19th centuries served as repositories for disseminating newfound knowledge—often motivated by emerging technologies. The "Atlas of Speculative Mineralogy," on the other hand, leverages the power of machine learning and deep neural networks to engage in a dialogue spanning both the past and the future. It revisits the practices, methodologies, and visions of naturalists from the 17th and 18th centuries through today's computational algorithms.

Naturalists of the past—motivated by a profound curiosity for uncovering the patterns of nature—embodied a multifaceted role as scientists, artists, publishers, authors, and editorial designers. They were polymaths. Today, our world exists as an intricate web of interconnected networks. While individuals may understand a sliver of these complex systems, comprehending its entirety remains an impossible challenge. Inspired by a polymath's ability to look across disciplinary knowledge, this atlas combines a wide array of practices and fields of knowledge to unveil unforeseen connections.

Scientific atlases of the 18th and 19th centuries served as repositories for disseminating newfound knowledge—often motivated by emerging technologies. The "Atlas of Speculative Mineralogy," on the other hand, leverages the power of machine learning and deep neural networks to engage in a dialogue spanning both the past and the future. It revisits the practices, methodologies, and visions of naturalists from the 17th and 18th centuries through today's computational algorithms.

Naturalists of the past—motivated by a profound curiosity for uncovering the patterns of nature—embodied a multifaceted role as scientists, artists, publishers, authors, and editorial designers. They were polymaths. Today, our world exists as an intricate web of interconnected networks. While individuals may understand a sliver of these complex systems, comprehending its entirety remains an impossible challenge. Inspired by a polymath's ability to look across disciplinary knowledge, this atlas combines a wide array of practices and fields of knowledge to unveil unforeseen connections.

The visuals introduced in this atlas are digital artifacts created and contextualized by a sequence of machine learning models. The source material for this process comprises a collection of specimens I collect during micro-expeditions. These day-long journeys lead me to carefully selected geological outcrops where I gather two categories of samples: (1) rocks representing the local geology and (2) human-made materials found in the vicinity, reflecting globally disseminated anthropogenic substances. Rather than utilizing traditional instruments and practices to examine these samples, the samples themselves serve as my instruments. They become extensions of my senses to look at our world—and our various histories of exploring it.

How many specimens do I need to initiate my investigation? I found the answer in the detailed records of Alexander von Humboldt's 1799 South American expedition. With an assortment of bags and suitcases—and with considerable support—Humboldt transported a total of forty-two instruments, including microscopes, a thermometer, a dip circle, a sextant, a cyanometer (for measuring the blueness of the sky), and various others. Inspired by this collection of specialized instruments, I am sampling forty-two substances as my working research objects. These substances are divided into two groups: (1) twenty-one rocks and (2) twenty-one anthropogenic substances.

(1) Rocks

The components of rocks are minerals. Minerals are substances formed by natural geologic processes without human intervention. An outcrop appears when a rock layer or formation is not covered by soil or other bio-material. It provides an opportunity to sample the local geology, often with a geological history spanning hundreds of millions of years. This atlas explores outcrops located within or near post-industrial regions and 20th-century transportation hubs. This exploration highlights the contrast between the outcrop's static geological location and the global mobility of everyday objects.

(2) Anthropogenic Substances

Our everyday lives depend on human-made substances. They allow us to travel, carry food, and even cure diseases. However, paradoxically, they pose simultaneously one of the most significant threats we face. In all likelihood, they will remain on this planet as witnesses of the Anthropocene beyond humankind. For this investigation, I am sampling substances based on their proximity to the previously designated geological outcrop. Their purpose, function, origin, or chemical composition are not relevant. When we deconstruct these artifacts, we may discover their components have traveled globally. In this sense, looking at these working objects reverses the conventional idea of a scientific expedition: not the observer but the observed objects have traveled across the world.

The components of rocks are minerals. Minerals are substances formed by natural geologic processes without human intervention. An outcrop appears when a rock layer or formation is not covered by soil or other bio-material. It provides an opportunity to sample the local geology, often with a geological history spanning hundreds of millions of years. This atlas explores outcrops located within or near post-industrial regions and 20th-century transportation hubs. This exploration highlights the contrast between the outcrop's static geological location and the global mobility of everyday objects.

(2) Anthropogenic Substances

Our everyday lives depend on human-made substances. They allow us to travel, carry food, and even cure diseases. However, paradoxically, they pose simultaneously one of the most significant threats we face. In all likelihood, they will remain on this planet as witnesses of the Anthropocene beyond humankind. For this investigation, I am sampling substances based on their proximity to the previously designated geological outcrop. Their purpose, function, origin, or chemical composition are not relevant. When we deconstruct these artifacts, we may discover their components have traveled globally. In this sense, looking at these working objects reverses the conventional idea of a scientific expedition: not the observer but the observed objects have traveled across the world.

— GANs & Image Classifier

Photographs of the specimens serve as the training data for Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), enabling the creation of novel, unexplored, and speculative visual hybrids. As James D. Dana expressed, "I find abundant pleasure in examining the forms and varieties of structure."

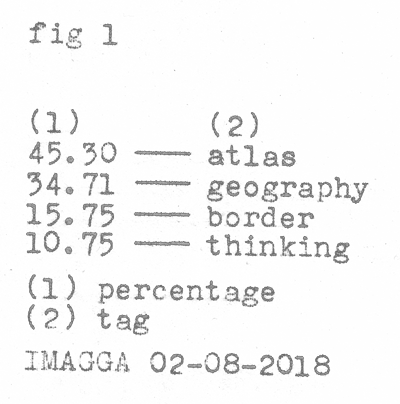

How would a machine—lacking my emotional access and my aesthetic appreciation—read this artifact? To gain insight into how such an apparatus would interpret this artifact, I feed the visualizations to a third algorithm: an image classifier. This image classifier makes determinations based on the training it has received from other humans, along with their selection of training data sets, which may include their biases.

The machine's response is a list of tags. Keywords. Words and letters that appear arbitrarily juxtaposed. While the ideas behind these automated captions are meaningless to machines, they reflect the aspects of contemporary visual culture and language incorporated into artificial system training.

— Collections, Albums & Plates

The atlas is composed of albums and plates that are organized into collections. Furthermore, appendices present a more experimental investigation contextualizing the specimen.

The elusive and uncanny visualizations do not provide any evidence to verify a scientific hypothesis. Instead, they invite us to question our comprehension of the boundary between the natural and the artificial, the archive and the truth, the past and the future, and our material culture and rituals. What are the things we bring into this world, and what will we leave behind?

↗ OpenSea

Photographs of the specimens serve as the training data for Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), enabling the creation of novel, unexplored, and speculative visual hybrids. As James D. Dana expressed, "I find abundant pleasure in examining the forms and varieties of structure."

How would a machine—lacking my emotional access and my aesthetic appreciation—read this artifact? To gain insight into how such an apparatus would interpret this artifact, I feed the visualizations to a third algorithm: an image classifier. This image classifier makes determinations based on the training it has received from other humans, along with their selection of training data sets, which may include their biases.

The machine's response is a list of tags. Keywords. Words and letters that appear arbitrarily juxtaposed. While the ideas behind these automated captions are meaningless to machines, they reflect the aspects of contemporary visual culture and language incorporated into artificial system training.

— Collections, Albums & Plates

The atlas is composed of albums and plates that are organized into collections. Furthermore, appendices present a more experimental investigation contextualizing the specimen.

The elusive and uncanny visualizations do not provide any evidence to verify a scientific hypothesis. Instead, they invite us to question our comprehension of the boundary between the natural and the artificial, the archive and the truth, the past and the future, and our material culture and rituals. What are the things we bring into this world, and what will we leave behind?

↗ OpenSea